Here is some advice I have been giving to students who are interested in graduate school in linguistics. Some of it is a more detailed version of what you will find elsewhere, including on the NYU linguistics FAQ page for grad applicants. But some of the advice below is based on my own experience of reading applications, making admissions decisions, and advising honors theses. It doesn’t necessarily reflect how other people in the department think about these things, or how other universities do their admissions.

Should you apply?

Probably not. Grad school is not for everyone. Grad school trains you for a professional career. The primary skill you learn is how to conduct research, and this is a different skill than being “good at college”–you need creativity and an ability to function in a somewhat adversarial environment. Plenty of people who finish PhD programs do not succeed at getting jobs in academia, but the professors teaching you are primarily skilled at getting academic jobs. There are not many academic jobs. For example, in any given year, there may be anywhere between 5 and 7 tenure-track jobs for phonology nationwide in the United States. There may be as many as 100 candidates applying for these jobs. Of the jobs that are available, many will not be in universities or departments like the one where you get your PhD. Quite a lot of doctoral students end up working as adjuncts, with little job security or benefits. There are definitely easier ways to make a living, and there is a lot to be said for entering the job market right after college, so you can accumulate experience and retirement benefits earlier.

In addition to the job market being abysmal, the grad school environment does not agree with everyone. It is much more competitive than your college experience. All of a sudden, your coursework is also your job. Everyone else is asking smarter questions than you and has a longer and more impressive CV–or so it seems. Everyone else is presenting at conferences seemingly every other week, while you get rejections or end up with writer’s block. There is a ton of reading every week, and the homework is really hard. After the first year or two, there is no homework, but you are somehow expected to learn how to be your own boss and produce research without someone else setting deadlines for you. Some people thrive in this environment, but others find it miserable. Hint: your professors are probably people who did great in grad school, and they might tell you that it was the happiest time of their lives. But there are plenty of people who do not do well. You don’t know which type you are until you go through it.

Got all that? Good. Still want to apply? Sigh, okay. You should do it if you really love the idea of being a professor and cannot imagine doing anything else. After all, there are some great things about this job, and about grad school. Everyone around you is pretty smart–well obviously, they like the same things as you, so they must be, right? You get to make your own choices about what you study or write about. The schedule is relatively flexible. You get to teach and put mold in young minds (or something like that). So, how do you get in?

Before You Apply

You need to start thinking about this early, probably in your sophomore year or early in your junior year. The reason is that you really need to do some work at the graduate level, both to ensure that you can function in that setting and to show to the programs you are applying to that you know what you are getting into. So, you take whatever basic undergrad courses you have to early, and then take graduate courses–we let undergrads enroll in those with the professor’s permission.

A graduate course will usually require you to write a term paper. A standard part of any grad school application is a writing sample. The writing sample demonstrates both your ability to do research and your ability to write, so it is essential. And the fastest way by far to produce a good writing sample is to take a graduate or advanced class.

Writing Samples: Dos and Don’ts

- Do include at least one writing sample in your area of interest. An application from someone interested in phonology needs to include a paper on phonology. Even better if your paper is in a specific area that you describe in your personal statement.

- Your writing sample must be proof-read, not just by you but by a professor in your area of interest. Make it shine.

- Your writing sample should not be a first draft. If you cranked the paper out on the eve of the due date on Adderall and haven’t looked at it since you got a grade, and you never did anything with the comments, you are not grad school material. Let me repeat that: people who do not make use of the comments that their professors painstakingly write on their papers are not good candidates for grad school.

- Do include several writing samples, as long as they are all of decent quality (thus, all have been through at least one round of revisions). NYU officially asks for one, but you can append multiple PDFs. I personally like to see evidence of range.

- Research on an original topic of your choosing is the best kind of writing sample. If a paper includes a lit review but no new ideas of your own, it should not be the only thing in the packet.

- Do include a little note, if necessary, that explains what each of the samples is about and its history. For example, I assign a final project in my phonology class that involves making up a problem and coming up with a solution (hat tip to Beverley Goodman, who assigned such a project in my first phonology class). But if I were to include such a piece as one of my writing samples, I would also explain what the assignment was. Term papers usually stand on their own, but you can still explain that the paper was written for a seminar, or is not in your main area.

- I do not recommend including papers from courses unrelated to linguistics. I rarely look at such papers, and I wonder why they are in the packet (especially if there is no linguistics sample).

- Do not include subpar work just to pad your application out. Do not include every exercise and problem set you ever did in a phonology class.

- Very long papers will probably not get read closely (50+ pages is on the long side), but if you have an MA thesis and it’s your best and only written work in linguistics, then of course you should include it.

I hope this clarifies why it is a good idea to take multiple classes that include a term paper as a component. You want to give yourself options.

Personal and Research Statements

When I was applying to graduate school, there was only one statement, but now some departments (including NYU) ask for two, and students often don’t know what the difference is.

The research statement is sometimes called “Statement of Purpose”. This is the essential document that explains what you plan to do in grad school, what your specific interests are, and what you have already done. A good research statement is specific: it is not enough to say you are interested in phonology, or even in stress or syllable structure or whatever. The statement needs to show your familiarity with theoretical issues or your experience in designing and running experiments. I also like to see more than one potential area of interest, with some specificity. Graduate programs usually require that you write two qualifying papers in distinct areas, and it is good if you already have a tentative plan for what those might be. You are allowed to change your mind later.

Should you mention specific potential advisors? It’s not essential. NYU’s online application system does ask applicants to check names of “people of interest”. You do not need to name-check every faculty member in the department in your statement. But if you do mention specific people, make sure you know what they actually work on and what kind of advising they have done. When in doubt, leave it out. At the very least, talk to faculty in the same area before you mention people.

It should go without saying that your statement should be read by a professor before you submit it.

Personal statements are optional at NYU, and I wouldn’t submit one myself unless I absolutely had to. I just assume that nobody wants to hear my life story. I also have seen quite a wide range of things that people put in these statements. Sometimes it’s relevant to the grad school application, but often it is not. So, my advice is to write whatever is relevant to the grad school application in that statement. For example, your path toward the decision to apply could be described there; whether it’s your childhood love of dictionaries or your chemistry MA that didn’t work out. Corollary: I don’t think that stuff needs to be in your research statement. I would make that strictly about your research interests, not your life story.

CV, transcripts, tests

Transcripts are usually not optional, and they are usually self-explanatory. If there are any blots on your transcript–any grade of C or lower, I’d say–then I would include a note if you have an explanation for that.

The Curriculum Vitae is a document that summarizes your professional experience. You should take a look at CVs of faculty and grad students on the department websites for examples and inspiration. Ideally, you have something like a conference presentation and maybe some research assistantships to include. It isn’t expected to be long.

Tests such as the GRE used to be a normal part of the application but have been largely phased out. If they come back, find out what a decent score is, and sit the test twice if necessary. For the GRE, the raw score would come with a percentile, and you’d want to be somewhere in the top quarter of the pack in every category. Linguistics involves quantitative and verbal reasoning, so having abnormally low scores in either area is a worrying sign.

Letters of Recommendation

- You usually need three of these. Ideally they come from faculty who have seen your research, so again taking a wide variety of high-level courses is essential.

- You should ask your professors early–not two days before these letters are due. I would give them at least a couple of weeks.

- You should verify that the professor is able to write you a strong letter. If the answer is no, find someone else. (But also ask yourself if you have some self-improvement to do.)

- Finally, if you are asking more than a semester after you took the class, remind the professor what kind of work you did for the class. I can usually reconstruct this from my records, but it is better if the student provides me with some clues.

The Interview

We do Zoom interviews with people whose applications caught our eye. Many schools do not. Some schools will invite their top choices for a campus visit and make the decisions only after the open house is over.

So, how do you prepare for the interview? I would ask a faculty member to give you a mock interview. You should expect to describe your research interests, and your past experience as well as future plans. You might get follow-up questions about your writing samples, so make sure you are prepared for some grilling. I would even go so far as to ask to be interviewed in the same medium as the grad school will be using: for a Zoom interview, practice on Zoom.

When doing a video interview, you need to pay attention to whether the people are still listening to you, and make sure you do not talk too long. Ask follow-up questions: “Did I answer your question or would you like more detail?” That kind of thing.

The Waiting, and the Waitlist

Usually you can expect to hear something by mid-February. If you get in, great! If you get multiple offers, discuss them with your professors. The schools would like to know what you plan, either way, as soon as possible. A quick “no” is useful; grad schools compete for some of the same candidates so they do not expect everyone they offer admission to say yes. Quick decisions also allow them to move on to the waitlist if needed.

When I applied to grad school, I got waitlisted at all three programs. Then, right before April 15, I got offers from all three. (Looking back to my application, I can see why I didn’t make the first cut: even though I had taken a ton of classes, my writing was awful. One of my professors gave me a writing book, Williams’s Style: Clarity and Grace as a parting present. Perhaps it was a hint.)

Don’t take it personally if you get waitlisted or rejected; sometimes it has nothing to do with the quality of your application. It can matter, for example, whether other subfields in the department have enough students. At NYU, we have a target every year (e.g. 6 or fewer admits). If we get too many students in one year, we are often not allowed to make many offers in the following year, so many good applicants get rejected.

If you do not hear from anyone for a long time after applying, it is fine to write to the department and ask when and whether decisions have been made. Do not expect a detailed explanation of why you didn’t get in. But you shouldn’t just submit the same application again to the same programs. Talk to your professors, but one option would be to apply for a Master’s, possibly in a European university where such programs are more plentiful. You can also find a gig as a lab manager, either in the US or abroad. That kind of experience greatly boosts your chances of succeeding the following year.

If you are applying to the same program for the second time, you should make clear what is different in your application this time around. I would put that information prominently in the research statement (which is usually the first part of the application I read).

The Honors Thesis Option

Now we get to the Honors thesis. I generally do not recommend this option for students interested in grad school. The reason is that the thesis takes too long. Deadlines for grad programs are usually in December or so, and theses are not completed till May of the following semester. You shouldn’t send an unfinished thesis, and if all you have is the proposal, you will not stand out compared to someone with extensive research experience.

In Italy in the 1970’s, everyone who went to college had to write a thesis. Apparently it was such a nightmare to advise these that Umberto Eco wrote an entire book explaining what a thesis is and how to do research for one, and how long it takes. Look it up: it’s called, shockingly, How to Write a Thesis. It is very good, and it has much of the same advice that I have given to students for decades.

In American universities, theses are not usually required, though some schools do have this requirement. Most just make it an option for graduating with honors. Is it worth doing a thesis just so you can graduate with honors? Honestly, I don’t think so. If you plan to go on the non-academic job market, nobody cares what grades you got, or whether you got honors. They probably care that you went to college, and possibly which one. But even that might be a thing of the past. Talking to non-academics about this, the general consensus I got was that any job that asks you for your GPA or whether you got honors in college is one you should run from.

Also, pragmatically, an honors thesis is a dubious preparatory experience for non-academic life. You learn to write something quite long, while real life usually requires you to be brief. You write for an audience of two people (thesis advisor + reader), on something quite obscure. You do learn how to organize information and go deep into a subject, but there are other, more useful ways of doing that.

For the rare few who write a thesis after having completed many good term papers in advanced courses, of course, the thesis demonstrates the ability to engage with a long-term research project and to write regularly. I have seen this come to fruition exactly twice in my teaching career, and neither thesis ended up being developed into a publication.

If you are intent on writing a thesis anyway, here’s my advice.

- Take an advanced class, preferably a grad one, in your area, and test-drive the topic as a term paper first.

- Establish a relationship with a professor, ensuring that your styles mesh. I tend to want regular, timely work. If your style isn’t like that, we won’t get along. It can go the other way: if you are prompt and diligent, but your prospective advisor does not give you feedback and is hard to reach, you should know before you embark on the project.

- The topic should be chosen with the advisor’s help. I usually recommend to all my students that they narrow things down to two or three topics, do enough research on each to explain them to the prof, and select among them with the prof’s help. Do not just bring the topic to the prof as an ultimatum; it needs to be a two-way street.

- If you intend to use the thesis as a writing sample for grad school, you either need to complete the writing and revisions before December or apply in the year following your graduation.

Research Assistantships and Teaching

These fall under the category of ‘transferable skills’—probably more transferable than any honors thesis writing.

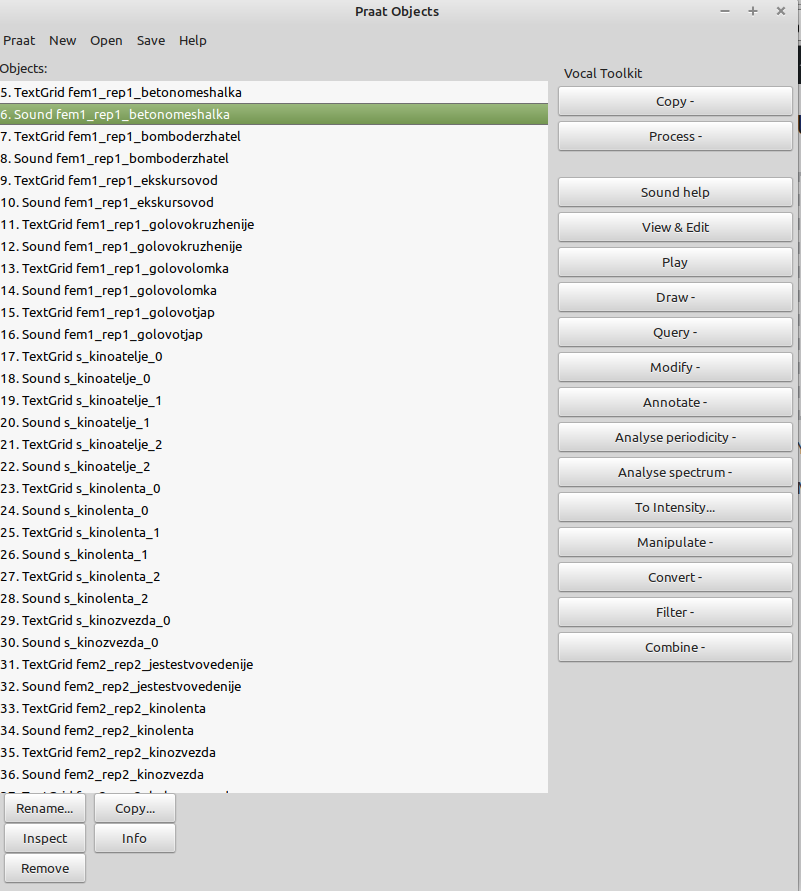

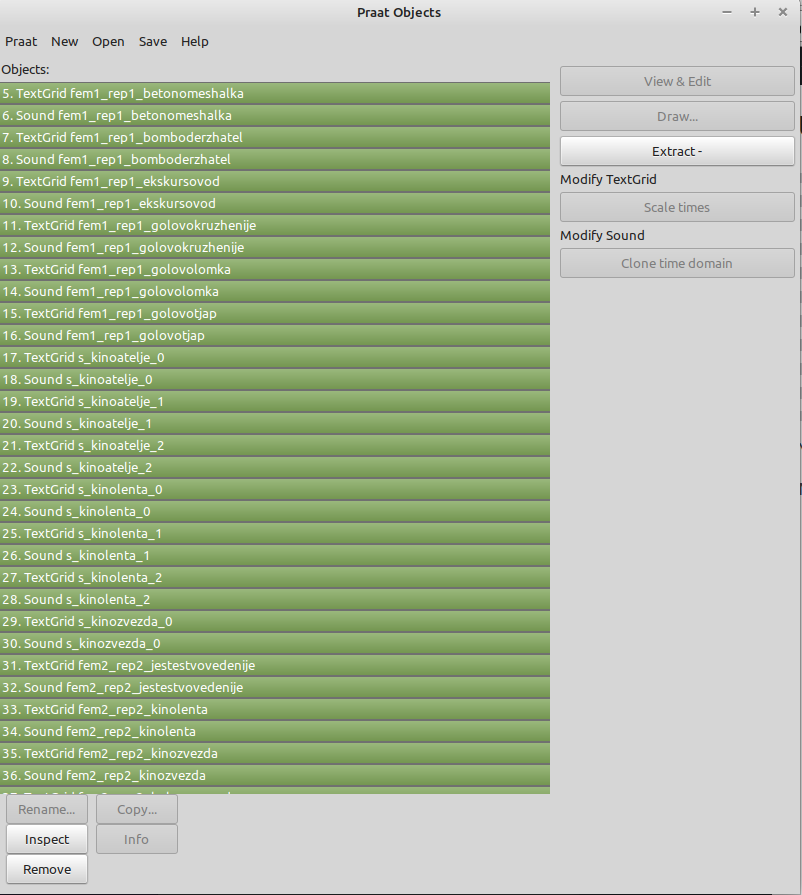

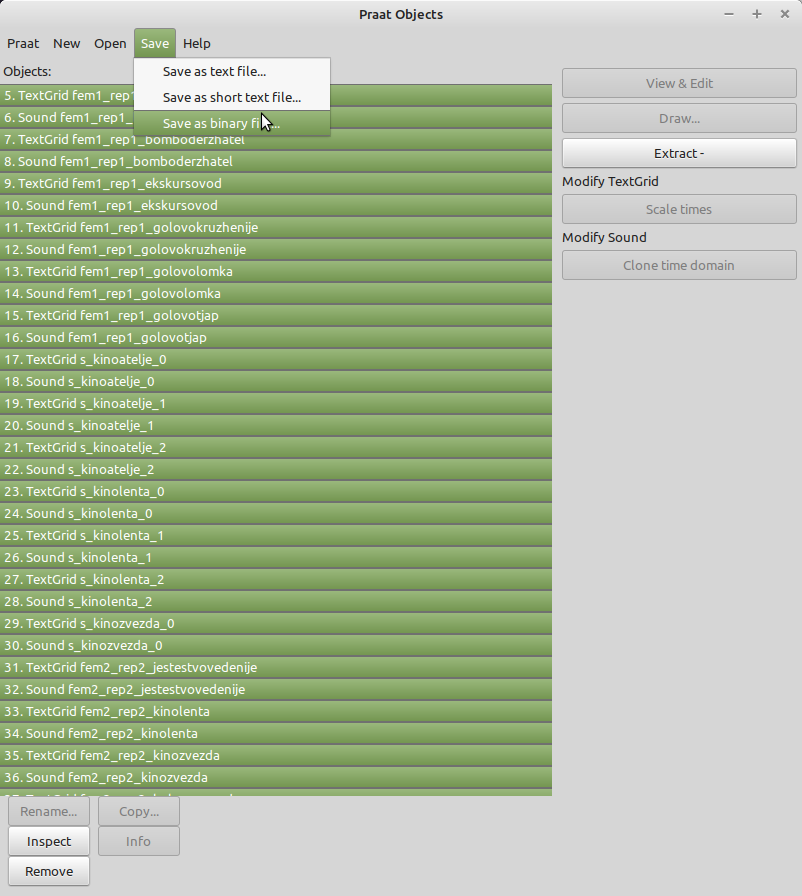

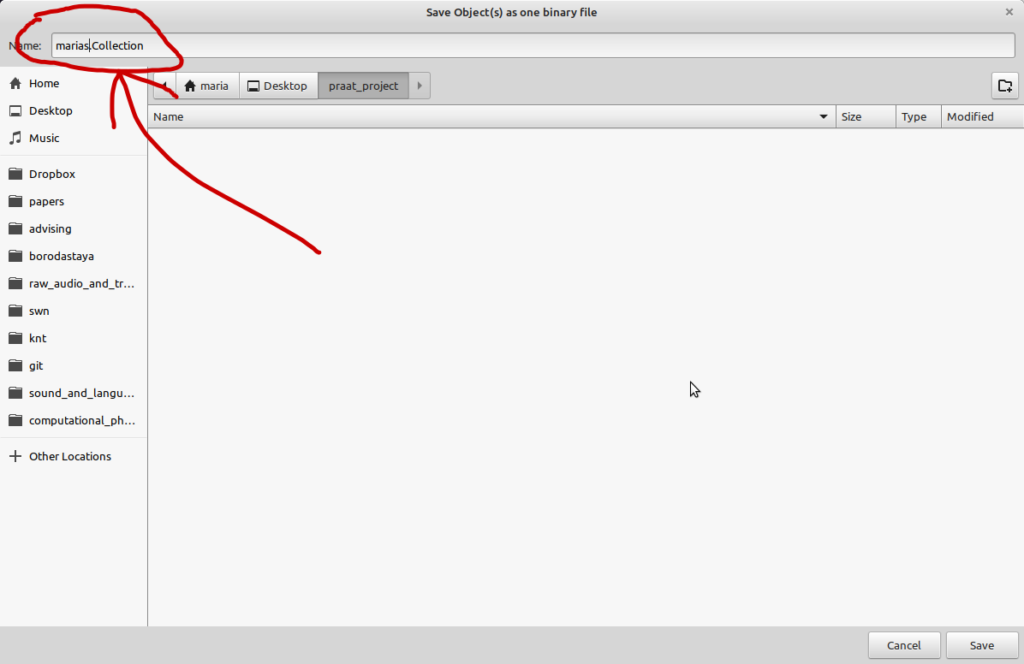

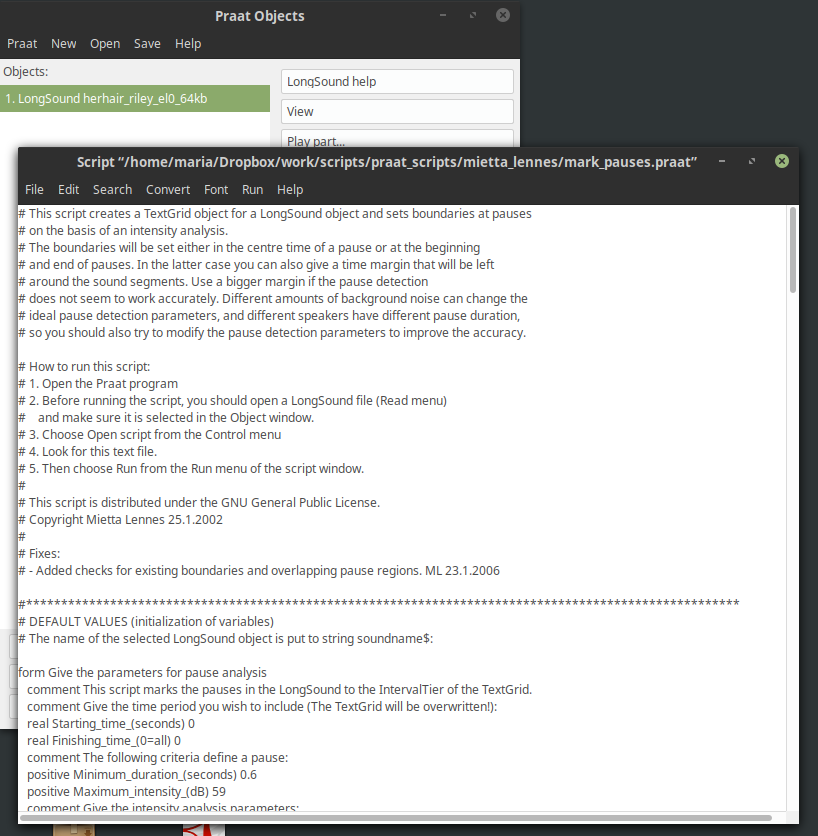

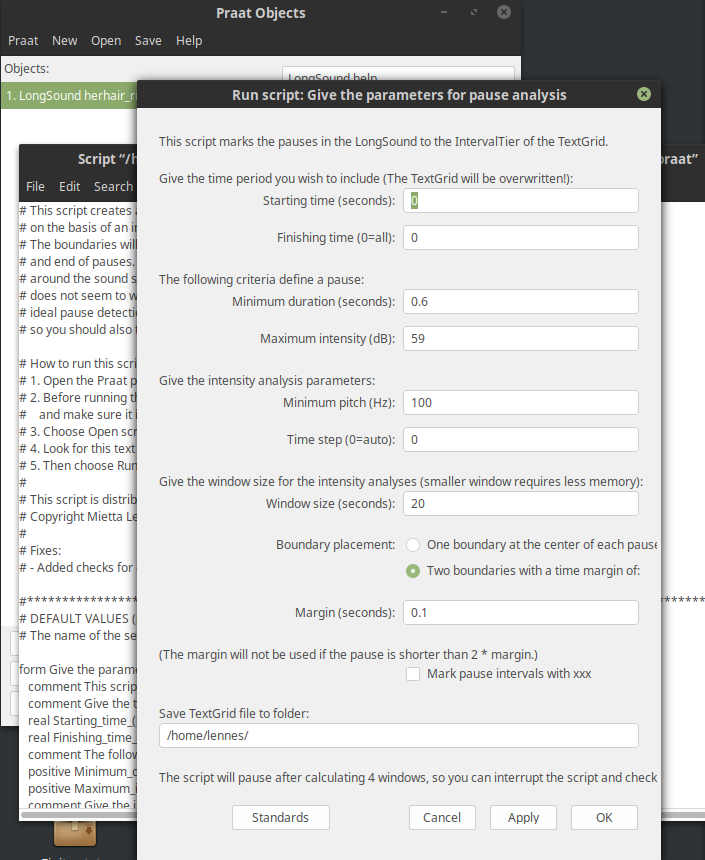

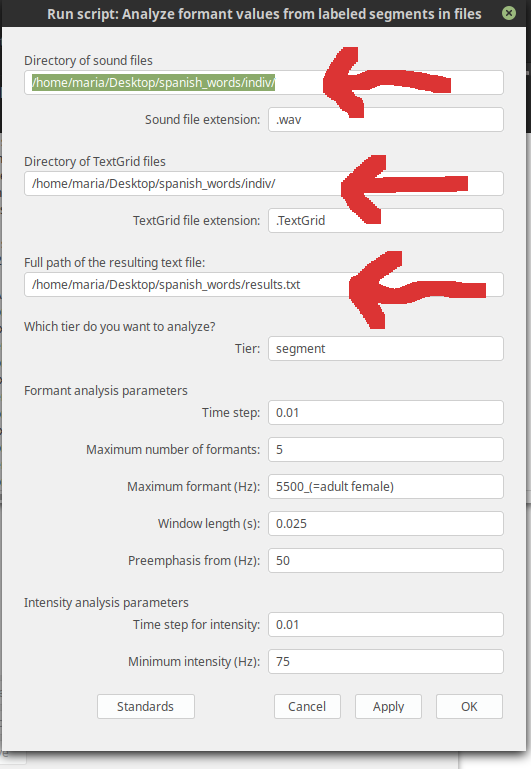

In a research assistantship, you perform tasks set to you by a professor. This can be data preparation or processing, or it can involve collecting data from experimental participants. RAs are often trained to use specialized software such as Praat. You might be asked to do some library research. When I was a student, I was asked to help a professor find video materials that could be useful in teaching an introductory linguistics course–this is somewhere between an RAship and a TAship.

At NYU, TA-ing is normally done by our own grad students, but we sometimes hire former BA majors, as well. TAs do grading, lead recitation sections, and occasionally have to prepare their own materials for teaching. TAs also often have to re-explain material that students either missed in lecture or didn’t understand on first pass, so they have to have a good grasp of the subject being taught. Even if you do not work as a TA, though, you can do some tutoring at NYU’s University Learning Center.

It is obvious how these skills would help in an academic job. But how do you transfer these skills to a corporate job? Well, you have to do tasks set to you by a manager, on a schedule. You also might have to train employees and supervise their work. Training involves breaking the activity up into separate easy steps, and you have to understand the activity fairly deeply in order to do that. So, you should seek out these opportunities if you want to acquire these skills.